Bank Robbers

About artwork

Provenance

Tech info

About

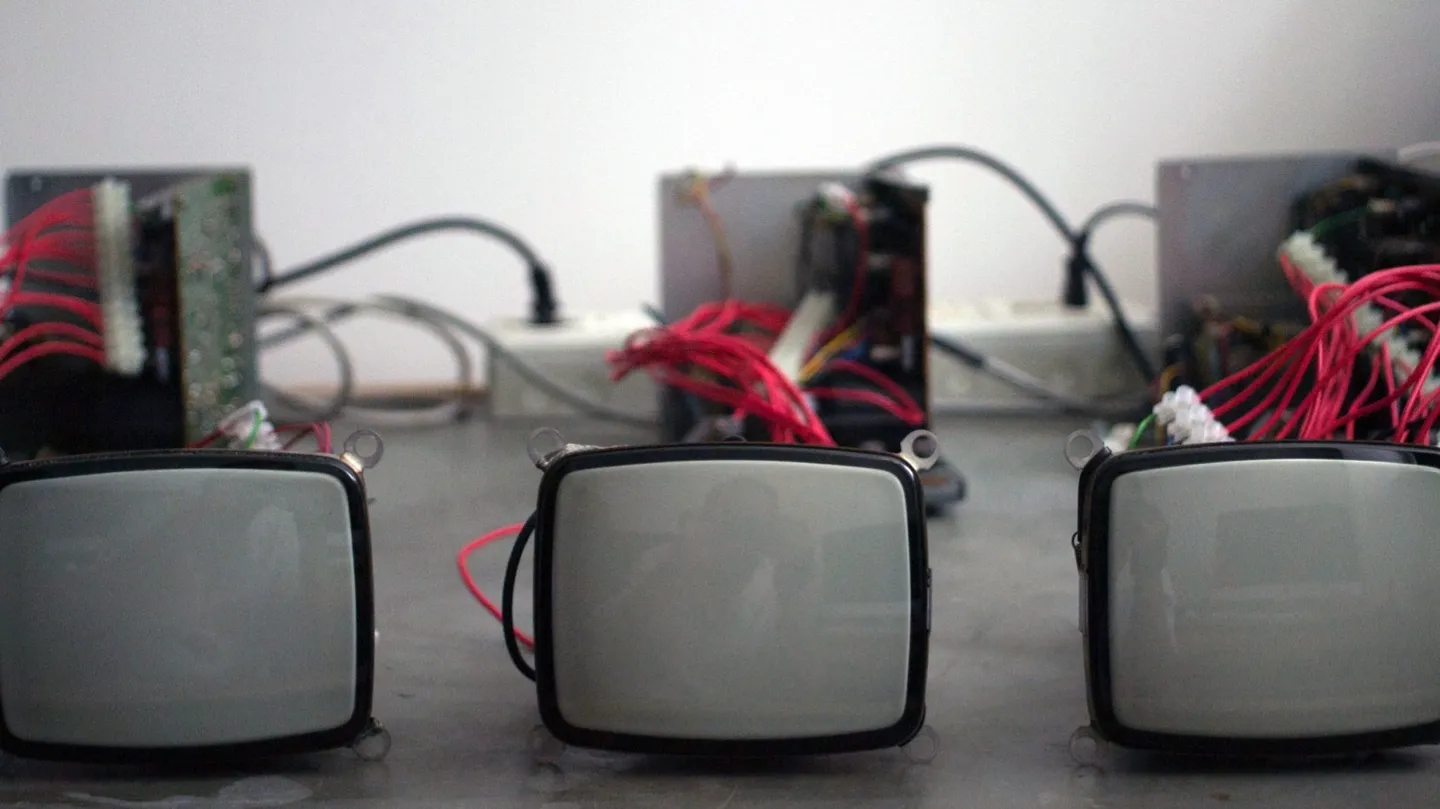

Seventh Commandment: You Shall Not Steal Breaking the law is generally considered a mistake—an ethical failure. Yet, both in life and in art, there are moments when transgression becomes not only inevitable, but necessary. Few crimes ignite the collective imagination as intensely as a bank robbery. The image of vaults full of money has long given wings to our fantasies. Bank robbery is a topic extensively represented and mythologized, not only by the news media but especially through cinema, to the point of becoming a genre in itself. From Bonnie and Clyde to the Dalton brothers to John Dillinger, countless films have contributed to shaping the myth of the "authors" of great heists. Interestingly, in common language, the word "author" is often used to describe someone who commits a robbery—as if they were creating a book, a film, or a work of art. In this sense, a bank robbery becomes an artistic gesture. This video installation is presented in two channels, juxtaposing reality and fiction—because in the history of heists, life and cinema continuously feed one another. Real robberies inspire movies; movies inspire real robberies. – “Hands up, this is a robbery!” – “Please don’t shoot!” These familiar lines, drawn from both life and film, reveal the porous boundary between documentary and performance. The ambivalence of cinematic language opens a space for détournement—a situationist act of reappropriation that uses pre-existing images for new, critical purposes. In this work, images are not created, but stolen: excerpts from films (covered by copyright), fragments from bank surveillance footage—reclaimed and reassembled to tell another story. As Buenaventura Durruti, a political militant of the early 20th century, once said, "Bank robbery is a political act." Legend has it that he once handed a gun to a beggar, saying, "Take it—go ask the bank about your money." Today, the question remains: who is the real thief—the bank or the robber?